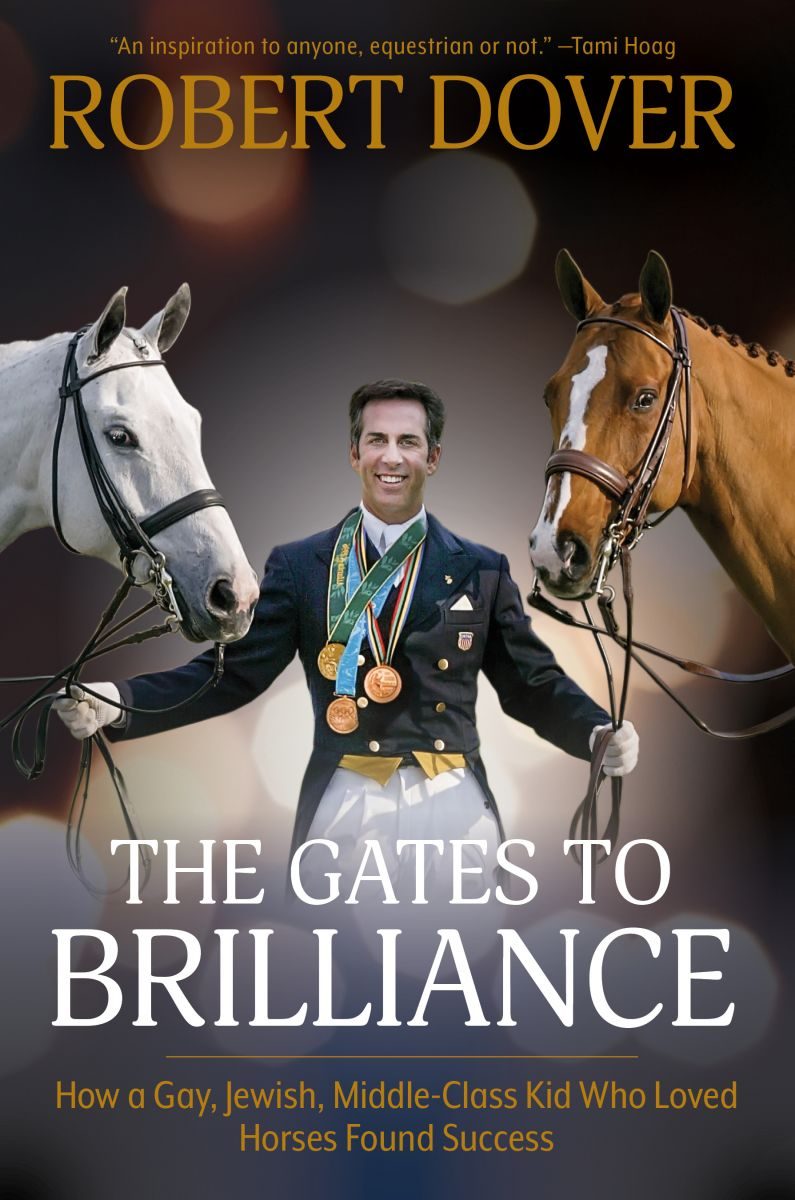

In this excerpt from The Gates to Brilliance by Robert Dover, the six-time Olympian shares the story of a major mistake on Roads and Tracks, and his first heartbreak.

Lisa was a senior from a high school near the University of Georgia campus. I fell madly in love with her. I spent every moment with her when we were not in class or working with our horses. I loved everything about her: She was beautiful, very smart, extremely mature, and always made me feel confident, even when there was really no reason I should.

Little things made me love her even more: The way she bound her two big toes together with a rubber band to keep her feet upright when she tanned in her back yard. Her Southern twang and boisterous laugh. And her unwavering passion for animals, which we shared. Most of all, the fact that this talented, smart, and beautiful lady could love a skinny Jewish kid with a big nose and crooked teeth—basically a geek in every possible meaning of the word—was to me a miracle!

We had been dating three years and I was twenty-one when a friend of mine, Francie Dougherty, who was in vet School at UGA, said I could borrow her horse to compete in my final National Pony Club Rally, which was taking place in Lake Placid, New York. The US Pony Club was the major source of training for kids twenty-one and younger, was responsible for launching the careers of the vast majority of our equestrian Olympians.

So, competing at the highest level achievable in this organization, as an “A” Pony Clubber, was to be the highlight of my life up until then. I asked Lisa to drive up with me and Francie’s horse for moral support, and I was thrilled when she agreed. Off we set on our great adventure.

Lake Placid was gorgeous, and the stage was set for a week of top competition. Lisa helped me where possible, but the nature of the Rally was that Pony Clubbers had to be responsible for all their own grooming and care of their horses and equipment, as it was judged as the “Stable Management” part of the competition.

Written tests were also part of Rallies, and points or deductions of points from these phases, as well as the ridden competition, determined the overall champion. As for riding, we had to perform three disciplines: The first was dressage at a Second or “Medium” Level. Next was a cross-country test of technical difficulty over a course of up to thirty-four obstacles and an array of combinations and questions that demanded superior skills. Finally, the third day we rode a stadium jumping course, which, with fences at a maximum height of 3’11” (comparable to a 1.20-meter jumper class), was a test of how responsive and fit your horse was after a hard cross-country course.

I was confident that I would do a good job in dressage as I normally did. Francie’s horse was also a very good, brave, and clean jumper, so I was pretty sure we could have a fine stadium jumping day. The problem I historically had was with cross-country. It was not that I feared falling or running out at a fence. No, my problem was that I always seemed to get lost somewhere out on the course. Once I got going faster than a brisk walk, I was famous for having zero sense of direction.

I decided that there was no way I was going to get lost in this, my very last Pony Club Rally. I walked the course not one but two times. Then, I was so determined that I actually ran it as fast as I could so that I would be prepared to make decisions more quickly as to which routes and turns to take. By the end of the day, I was exhausted but absolutely confident that I knew the course inside and out.

The next morning was the dressage test, and Francie’s horse went great, winning the class and setting us up in perfect shape for our cross-country day. A crowd congratulated me afterward, and I beamed at Lisa when I saw her fleetingly. She seemed to be enjoying herself socializing with people in the spectators’ tent. When I was competing, even back then, I was totally self-absorbed. Honestly, you need to be if you want to win.

The morning of cross-country, the horse and I were ready. But I had neglected to consider the one other phase of the competition, which mirrored three-day event competitions back then: “Roads and tracks” consisted of a very simple, brisk trot around a mowed track that was a very obvious square perimeter of a ten-acre field. It was basically meant to warm and loosen up the horses before they had to gallop and jump.

Easy enough, right?

Not for Robert Dover.

Off I went on my trot, noting as always the red and white flags that riders were to stay between on their ride around the field. As I came to about the halfway point, I clearly saw a red flag hanging from a tree and a trail going off into the woods. Not having walked the track, off I went

into the trees. A few minutes later we were heading down a ravine, and I eventually stopped at a rocky creek. I could barely see the path on the other side of the water, and the creek did not look easy to cross, but I was determined to win the competition and every second over the time limit to finish roads and tracks would cost me points.

My horse was not happy about the crossing, and we only made it halfway before he reared up, whirled around, and took me back the way we came. Deciding he had more “horse sense” than I did, I trotted him back up the hill, exited the woods where we’d entered, and saw plainly that we should have just stayed on the mowed path. We broke to a canter and then a slow gallop as I wanted to make up the time we’d lost but did not want to overtire my horse before the major test ahead of us on cross-country.

A few minutes later we finally finished, and my friends asked what had happened to me. I chose not to think or talk about my mistake, and instead prepared my horse to enter the start box where the next phase would begin. As the steward counted down, adrenaline coursed through my body. I was hot and sweating, nervous but determined as never before to go clean.

Francie’s horse was wonderful, taking each jump in stride with ease, and we finished the cross-country with no faults. He also jumped perfectly the last day during the stadium jumping. Had we not gone wandering during roads and tracks, we would have been the clear winner; however, the time we took to complete that simple trot around the field cost us…ONE HUNDRED TIME FAULTS!

ONE HUNDRED TIME FAULTS!

I was embarrassed and not a lot of fun to be around the last twenty-four hours of the event. Lisa obviously knew this, but she was enjoying herself and had made friends with a lot of kids, including a very handsome, Ivy-League rider named Tad from a well-known equestrian family.

Tad was well over six feet tall and pretty much the polar opposite of me in every way. Under usual circumstances, I would have been jealous of their friendship, but I was so single-minded and exhausted from the competition that it wasn’t until we were loaded up and on our way back home that Lisa and I finally had any time to really talk. We’d always been great at talking, and we covered everything—from the competition to getting back to Athens and school.

Hours into our drive, Lisa told me she had spent a lot of time with Tad over the weekend and that he had asked her out.

“I will always care about you, Robert,” she said quietly, “but I think it is time we faced the fact that our relationship is over. I want more.”

I was absolutely crushed and cried on and off the rest of the long drive home. Lisa was also upset, but she had made up her mind; I couldn’t talk her out of breaking up with me. Arriving back in Athens, we unloaded Francie’s horse at the barn, then I dropped Lisa at home, went back to my double-wide trailer, and fell into my bed, crying myself to sleep.

This excerpt from The Gates to Brilliance by Robert Dover is reprinted with permission from Trafalgar Square Books (www.HorseandRiderBooks.com).