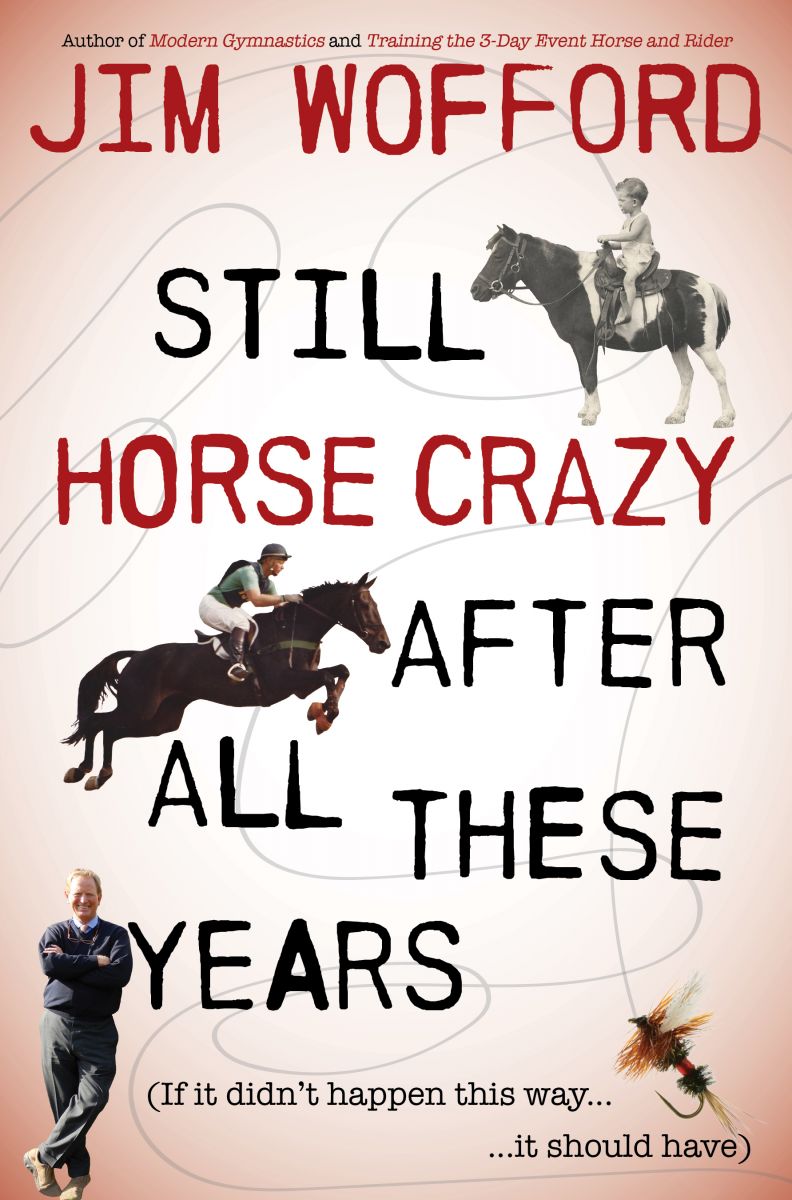

In this excerpt from his autobiography “Still Horse Crazy After All These Years”, three-time Olympian Jim Wofford talks about that time he came back from retirement to win Kentucky. “Still Horse Crazy After All These Years” is available in multiple formats, including audiobook, on HorseandRiderBooks.com.

Me, the Optimist

I got a call from Diana and Bert Firestone in the fall of 1985. Karen O’Connor (née Lende) was named to the 1986 World Championship team that would compete in Australia. Because the seasons below the equator are reversed, the Championship would take place in the spring, which meant Karen could not ride their horse, The Optimist, at Kentucky. Would I like the ride? With a recent Bill Steinkraus comment about getting better after retirement in the back of my mind, I didn’t give it much thought before I said, “Yes”.

Purchased by the Firestones as a ride for their son, Matthew, The Optimist (“Bill”) had turned out to be spectacularly unsuitable in that role. Matt was quite strong, but fairly short, and Bill was an enormous bull of a horse. I had been watching him go for a year or so and had always secretly liked him, even as I watched him run away with a succession of riders. I have a soft spot in my heart for 16.3-hand mealy-nosed brown geldings from Ireland, but at first glance it was hard to have a soft spot for Bill. He was unattractive: plain bay with no markings, slightly lop-eared, Roman-nosed, and pig-eyed, with a dull expression. He had a thick neck, massive shoulders, and powerful hindquarters. At first glance, in other words, he was the epitome of a thug.

The Firestones had several additional horses in training with Karen at Fox Covert, and I was fortunate that Bill’s groom, Janice Hilton, came with him. Janice was extremely knowledgeable, having worked for Lorna Sutherland Clarke in England before emigrating. She told me that if we got to Kentucky, it would be the one-hundredth Classic event she had worked at. (She didn’t tell me until much later that in all that time, she had never groomed a winner.)

Much to my surprise, within a couple of weeks of starting to ride Bill in January, I was thoroughly demoralized. No matter what I tried, we were not on the same wavelength, and I could tell we would not be successful if this trend continued. He resisted my efforts to get him on the bit and charged every obstacle in his path with a frighteningly powerful rush. After I had ridden him early one Saturday morning, once again with a signal lack of progress, I handed him over to Janice and went to teach some lessons in my indoor arena.

Bill, I See You!

Bill’s stall was next to the arena, and I had already noticed that he would hang over his stall webbing and watch my lessons. He focused his attention on the activity, and if I raised my voice, he lifted his head and pricked his outsized ears until the arena settled down. On this day, Janice returned him to his stall, and he audited the rest of my lesson until I finished. Then he turned his attention to his hay.

I didn’t realize it at that moment, but when I stepped from the arena into the barn aisle that day, I was stepping into the shadow of the rainbow once again. Bill heard my footstep outside his stall, and when he raised his head and looked at me, he looked directly into my eyes. His ears were up, his visage was attentive, and his eyes glowed with recognition and intelligence. Startled, I looked back at him—but suddenly it was as if his face were melting. In a flash his eyes were dull, his ears at half-mast, and he had assumed his normal lack of expression.

Laughing, I pointed at him and said, “Too late, Bill, I saw you!”

I suddenly realized that I had completely misunderstood Bill. He didn’t misbehave because he was stupid; he misbehaved because he was smart. (I did tell you he was Irish, didn’t I?) Bill did not need his rider to tell him what to do, or even worse, to try to make him do it. Bill knew his job; he wanted his rider to remember the test or the course—and leave the rest to Bill. If the rider tried to make Bill do something, he was just as happy fighting with the rider as fighting with the course. After all, as strong and athletic as Bill was, the jumping was not a challenge—and anyway, he didn’t care about dressage one way or another. But if a rider challenged Bill by leaving it up to him, Bill would respond.

Armed with new insight, I changed my approach, and Bill changed his way of going. I don’t mean that things were perfect after that, but we showed regular improvement. However, Bill wasn’t done teaching me new things. I’d already had my nose rubbed into the mistake of judging a horse by appearance. Now Bill taught me not to get tunnel vision when training event horses.

You can imagine that my morale improved after we won our first competition together, a nice Intermediate warm-up event in North Carolina. I had always done as little competing as possible when training Classic horses. Our cross-country and show jumping were nowhere near as technical then as in events today. I used my Classic preparatory events as a general fitness checkup and made sure my technical work was showing improvement. With only one more horse trials left before Kentucky, at Ship’s Quarters in Maryland, I felt pretty good about our chances. Our dressage work needed continual improvement, but that was no surprise. However, at our initial outing, it was apparent that our show jumping needed work. I had been lucky to leave the fences up. Even though the course had been slightly small and relatively easy, Bill had towed me around at a high rate of speed. This would not suit a big-time event.

While my conditioning plan was working, and my dressage improvement was slight but steady, I changed my show-jumping approach. I did a lot of jump-and-walk, jump-and-stop exercises, and worked on combinations with tight distances. Because I set these new problems and left them for Bill to solve, I thought I was happy with things by the time we got to our last “prep” events; it just goes to show you how wrong a fellow can be.

At Ship’s Quarters, traditionally the last event before Kentucky, everything was maximum but straightforward, not technical. It was just the right type of challenge to set horses and riders up for a Classic. I was already patting myself on the back halfway through my show-jumping course, thinking about how much better Bill was going. Then I turned into the triple combination. Set at maximum heights and spreads, it was a vertical, one stride to a maximum oxer, then two strides to another maximum oxer. I cantered quietly to the first element, Bill jumped it off a nice stride, and when I landed, what do you think I said to myself?

“Uh oh.”

I suddenly realized that I had practiced shortening Bill’s stride, but to the exclusion of increasing his stride. Long story short, I couldn’t get there from here. The only thing good to come from that particular in-and-out is that I learned not to have tunnel vision when training horses. Putting in two strides in a one-stride, three strides in a two-stride, and crashing through two maximum oxers will get a trainer’s attention. Bill’s courage and strength got me out of that scrape, but only just. Unlike my first outing with Bill, where I had won easily, I drove home in a bad mood with a lot on my mind.

My training from then until Kentucky emphasized flexibility, not just long or short. It must have worked, as I wound up winning Kentucky for the second time. Bill was not too far out of the lead after dressage, jumped clean and fast cross-country, and was in second place, less than a rail out of first, going into the show jumping. This was nerve-racking, as Bill was notorious for his casual attitude toward painted rails. However, I persuaded him to leave all the rails up, and once the rider ahead of me knocked down a rail they could not afford, I wound up a winner at my final Classic. After the disappointing finish to my Olympic aspirations two years earlier, this time I could retire on top. When I walked out of the arena following the victory gallop, I felt as if the eventing gods had reached down, patted me on the head, and said, “There, there. You were hugely disappointed not to go to Los Angeles. Now we gave you a big win, but it’s time you retired again, this time for good. Don’t push your luck.”

That was good advice, and I took it.

This excerpt from “Still Horse Crazy After All These Years” by Jim Wofford is reprinted with permission from Trafalgar Square Books (www.HorseandRiderBooks.com). Purchase your copy here.