In this excerpt from Anne Kursinski’s Riding & Jumping Clinic, Olympian Anne Kursinski tells us how she schools transitions in order to improve balance and self-carriage in all her horses.

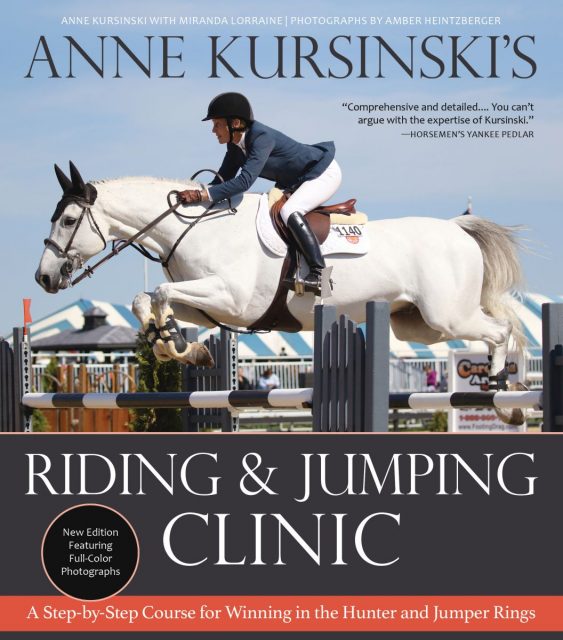

Photo by Amber Heintzberger.

Transitions — particularly downward transitions, both within a gait and from one gait to another — are a great way to encourage your horse to keep coming from back to front and to carry himself. You use leg to create whatever energy you need, hand to receive the energy and tell your horse what you want him to do with it, and seat to reinforce either the driving message of your leg or the containing message of your hand.

Whether the transition is upward or downward, you can also use your seat to make the change smooth rather than jarring by communicating to your horse the rhythm of the new gait that you want. Each gait has its own rhythm, of course: the four-beat walk, the two-beat trot, the three-beat canter, with variations depending on whether the gait is working, extended, or collected. I find that if you think the rhythm of the new gait that you want (like humming a song in your head, without making any audible noise), your seat and legs will automatically start telling your horse about it as you ask for the transition — or even as you’re just preparing to ask. The higher the level of communication between you, the more quickly he’ll pick up on your message and the smoother the transition will be.

If you want to go from the walk to the trot, “thinking” the trot rhythm will make your legs close a little more quickly, in the one-two of the trot, and help your horse pick up the rhythm in his body. As you feel the one-two rhythm begin, your upper body automatically tips slightly forward to stay with his center of gravity.

In a downward transition, say from the canter to the trot, putting the rhythm of the trot stride into the half-halts that you give while still cantering will let you make a smooth, balanced transition.

Downward transitions tend to be the bumpiest, because your horse has to shift his balance backward from where it’s been in the faster gait. (For the same reason, downward transitions are also where he’s most likely to become crooked — so you, as the brains of the operation, have to be on the lookout for straightness problems and be ready to apply appropriate corrections.) As you start taking his mouth to tell him to slow, he’s probably going to grab the bit — and pull you out of the saddle if you’re not ready for him. Here’s a place where thinking the rhythm really helps:

Quiet the swing of your hips and sit against your horse more, using your almost passive seat as a very short push against rather than with the motion to tell him you want shorter strides. I keep my hips relaxed, eyes up, elbows just in front of my hip bones — so my reins are a comfortable length and I’m thinking about my half-halt. I deepen my heels (think of yourself “growing” in the saddle), close my legs against the horse so that he gets off his forehand and comes up under himself (remember, any time he pulls against you, leg is what gets him light), and then take his mouth briefly, bending my elbows to ask him to stay light in front. Keeping your elbows bent prevents him from pulling you down and forward and keeps his poll up so that he stays off his nose.

When he answers the half-halt, I reward him by relaxing my elbows and easing my feel on his mouth, so that he knows this is what I wanted. I relax my legs as well, to tell him to trot, and “think” the trot rhythm with my seat. As he gets the trot rhythm, I make sure we maintain the nice, light balance, closing my legs to keep him moving actively into the bit from behind.

If your horse is very heavy, your first couple of “takes” may look rather jerky, because he’s going to expect to have something to lean on — so he’ll take more when he feels you give, which will make your next take have to be more forceful. Think of the motion as “lifting” him into the slower gait — so that he “sits” more behind and doesn’t fall down in front. As your horse finds out that you aren’t willing to let him balance himself by pulling against you, he’ll lighten and not fall forward so much.

And if you strengthen your leg or even add a prick of your spur the instant you feel him pull, you’ll accelerate the “Carry yourself!” learning process.

Keep sitting and lifting him slightly with your half-halts, bending your elbows. As you feel him trying to fall on his nose, sit in and sit up to bring his center of gravity back. With repetition, he’ll come to recognize that, when you open your hip angle and sit a little more deeply, you’re going to be asking him to come back — so he’ll start to do so on his own, and you’ll have less of a tug of war.

(That lifting feeling in your arms during the downward transition, by the way, is not a static pull but a little circle, resisting very slightly toward you, up, and forward again. The canter, particularly, is a circular gait in the way the horse comes off the ground into a moment of suspension, through the air, and then down again; your hips and your arms should have that same motion of lifting and giving, lifting and giving. You’re resisting in rhythm until he lightens, taking and giving in direct response to how strong he is against you.)

This excerpt from Anne Kursinski’s Riding & Jumping Clinic is reprinted with permission from Trafalgar Square Books (www.HorseandRiderBooks.com).