Olympic eventing has shape-shifted quite dramatically over the years, with early editions being nearly unrecognizable side-by-side with the modern sport. As we approach the 2016 Olympic Games in Rio, and with so much discussion taking place about where to take the sport in the future, we’re taking a look back at its evolution over the past century.

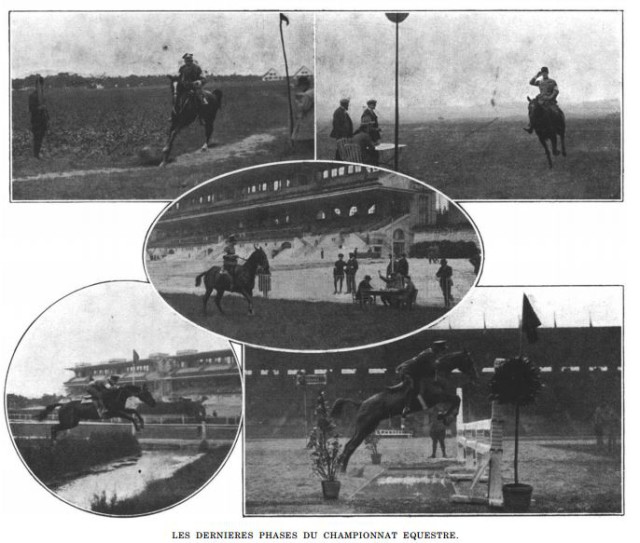

Scenes of Eventing at the 1924 Summer Olympic Games in Paris. Photo via the IOC report, public domain

The Roaring Twenties were not kind to the U.S. on any number of levels: Shell-shocked and wounded veterans of World War I were returning home, Prohibition was enacted (I WOULD NOT LAST ONE DAY OF THAT NONSENSE), and the final blow would come with the stock market crash in 1929 that kicked off the Great Depression. The era was no kinder to the American eventing squad, as there would be almost no Olympic glory earned in the 1920s. But the “almost” was earned thanks to one shining performance in 1924 by U.S. Army Major Sloan Doak and and the aptly named Pathfinder.

Sloan Doak had a lifelong interest and devotion to horses which would lead him into the cavalry in his youth. He was an incredible talented polo player, and his army mates at West Point recalled, “The stirring days in the riding hall, where Sloan’s superb horsemanship was displayed, taking four horses abreast over the jumps, dismounting and mounting at the gallop, facing to the rear as the fourth horse cleared the obstacles.”

He was a member of the 1920 Olympic Team which struggled to find its moment of glory, but it was nonetheless an incredibly educational experience for each of the officers, including Sloan. The Army Major would dedicate the next four years of his career to making good on that education, and building up a team and a horse who could get America on the board.

The team trained for the Olympics exclusively for a year at Fort Myer, Virginia and attended several events leading up to the games before heading abroad.

Pathfinder was one of fifteen horses shipped to Paris on May 31, 1924 for the U.S. Team, and six were cavalry horses, including Pathfinder. Several others were either owned by their riders (who were also Cavalry men) and only two were privately owned horses on loan to the American team. Of the horses who ultimately contended the games, Pathfinder was the only Thoroughbred.

After arriving by ship and train to Rocquencourt, France, the horses had to be reconditioned after a long journey, and with only a month before the Games. In the grueling training process, the country’s three best horses went lame and had to be eliminated from consideration.

When the competition began, things almost immediately went south for the Americans. Except for Sloan, the dressage tests by the Americans were middling to terrible. It turns out it was no dressage show, but that didn’t help our cause. Captain V.L. Padgett on Little Canada (I smell treasonous sabotage, with a name like that) and 1st Lieutenant F.H. Bontecou on Bally MacShane were unable to finish the endurance element of the event, which required 36 kilometers (around 22.5 miles) of endurance, cross country, flat racing, and steeplechasing on what turned out to be a brutally hot day in June.

Sloan and Pathfinder carried on in spite of the team’s losses, and produced a remarkably fast and clean day of endurance, which left them in third place going into show jumping.

Show jumping occurred on a sand track in the stadium, and was a test over twelve elements in two minutes. The test was much more like the old show jumping courses at Hickstead or Aachen, involving open ditches, brooks, and manufactured terrain, and there were only four clear rounds in the day.

Sloan and Pathfinder strutted in as if the hope of the country were not upon their shoulders, and the previous day had been a walk in the park, and nearly produced a perfect round. Their only trouble was a fault at the Brook element, but it was enough to secure an Olympic Bronze Medal, and the only medal of the 1920s for the United States Equestrian Team.

Individual Gold and Silver were awarded to Adolph van der Voort van Zijp of the Netherlands and Frode Kirkebjerg and Meteor of Denmark, respectively.

Major Doak would again represent the U.S. as captain of the team in 1928, where he finished 17th. 1928 would be his final time representing the United States as an athlete at the Olympics, but not the end of his Olympic story. In 1932 when the games came to the United States, Sloan was the Chairman of the Olympic Equestrian Jury, and was the first American to hold the esteemed title in history.

Sloan held many other esteemed positions in his life, including judging at Madison Square Garden’s National Show, President of the American Horse Show Association, and a life long military man with a 35-year career of service – all this despite the fact that he suffered from serious chronic pain throughout his life.

At the 1932 games, the U.S. would fire on all engines and make one of the most tremendous comebacks in the sport’s existence. Be sure to keep following our Weird Olympic History series to find out what happens next!

You can also check out the 1924 IOC report (which is in French, unfortunately!) here, and the U.S. Olympic Committee Report here.

Previous Editions of Weird but True Olympic Eventing History:

[History of the First U.S. Medalists]

Go Eventing.